One of the key focal points of user-centered design is the context in which the designs will be used. For technology products and services, contexts of use include a potentially broad array of factors—physical and social environments, human abilities and disabilities, cultural issues and similar.

Show Hide video transcriptContexts describe the actual circumstances of use. While not all of the aspects mentioned above apply in each case, it is important to consider what is and isn’t relevant. For example, almost all products and services operate within a legal context that requires them to be operable by people with disabilities. Other legal contexts govern the use of personal data – the GDPR in Europe, for instance—the ages for which certain content may be shown, along with strict laws in some locations around gambling and betting.

Environmental and physical contexts may not be particularly relevant to most websites, but this can change dramatically for systems used outside the typical home or office. Examples include external Automated Teller Machines (“cash machines” or “cash dispensers”), computing systems used in farming—some of which must be steam cleaned—and systems used for stock control in unheated warehouses or, more challenging still, cold stores.

User research and observation is essential to determine context of use. The goal of these processes, which include contextual interviews, user visits, etc., is to answer key questions such as the ones suggested by the leading UX consultancy Experience Dynamics:

In user-centered and user experience design, one of our main concerns is usability. The international standard on the ergonomics of human-system interaction (see Learn More About Contexts of Use) defines usability as

“…the extent to which a system, product or service can be used by specified users to achieve specified goals with effectiveness, efficiency and satisfaction in a specified context of use.”

Notice that the very definition of usability depends on the context of use. This isn’t hard to understand outside of software systems. However, contexts are usually overlooked because contexts of use are outside of the normal considerations in most software development methods.

The standard goes on to describe the components:

“The context of use comprises a combination of users, goals, tasks, resources, and the technical, physical and social, cultural and organizational environments in which a system, product or service is used.”

This is a much broader definition of contexts than is used in practice, but it is complete. Less formal definitions tend to group users, goals, tasks and resources separately from the environments as described above. However, the benefit of grouping all of these elements together becomes obvious when considering how the standard describes achieving usability in design and development. The steps are:

1. Understand and specify the context of use.

2. Specify the user requirements, including usability considerations.

3. Produce design solutions making use of the above.

4. Evaluate the design solutions.

When referring to a complete system, the context of use would include all users along with their respective goals, tasks and the required resources as well as the environmental contexts across all of those factors. These include

The context of mobile use is very different from that of desktops. It will require a different approach, such as context awareness, mobile-first or task-oriented design. In this video, Frank Spillers, the founder of Experience Dynamics, shares practical tips on how to understand the context of use in mobile User Experience (UX) design.

Show Hide video transcriptResearchers Savio and Braiterman introduced the “overlapping spheres of context” to a mobile user’s context that included:

Mobile experiences that factor in the context of use will be more likely to be successful than designs that are made for a generic audience with a one-size-fits-all approach.

Find here a research study into contexts of use and user experience.

Detailed article on the role of contexts of use in usability (PDF).

See Nadav Savio and Jared Braiterman’s original paper about the context of mobile interaction at Academia: Design sketch: The context of mobile interaction.

Nick Babich offers comprehensive and practical recommendations for designing mobile experiences in a Guide To Mobile App Design at UX Heuristics.

To learn about the differences between context of use and ease of use, read the How to explain Ease of Use vs Context of Use to your boss article by Frank Spillers.

Do you want to improve your UX / UI Design skills? Join us now

You earned your gift with a perfect score! Let us send it to you.

We’ve emailed your gift to name@email.com .

Do you want to improve your UX / UI Design skills? Join us now

Here’s the entire UX literature on Contexts of Use by the Interaction Design Foundation, collated in one place:

Before we dive into design approaches for mobile, you need to understand the context of mobile users and their unique characteristics. That means you need to know when, why, and under what conditions and constraints users interact with your app or mobile content. If you, therefore, understand the big picture (context) of a user’s interaction with a device—the social, emotional, physical, and cultural factors—you can create better user experiences. This will help you differentiate your app from others and get more people to use yours.

In this video, Frank shares practical tips on how to be more context-aware to understand contexts of use and apply it to mobile user experience (UX) design.

Show Hide video transcriptAs you can see, the mobile context varies from person to person. People don’t pay full attention to their smartphones as they do with desktops—remember that mobile users are on the move. They may be looking out for a cab at a noisy intersection (with details of their cab ride on their phones), jogging in a park (while listening to music), or scrolling through their social media feed while waiting for food at a restaurant. In each of these cases, we can’t—and shouldn't—expect them to be fully attentive to their devices. As Luke Wroblewski mentions, they use “one hand, one eyeball.”

“People use their smartphones anywhere and everywhere they can, which often means distracted situations that require one-handed use and short bits of partial concentration. Effective mobile designs not only account for these one thumb/one eyeball experiences but aim to optimize for them as well.”

— Luke Wroblewski, Product Director at Google

To better understand user context, you should consider:

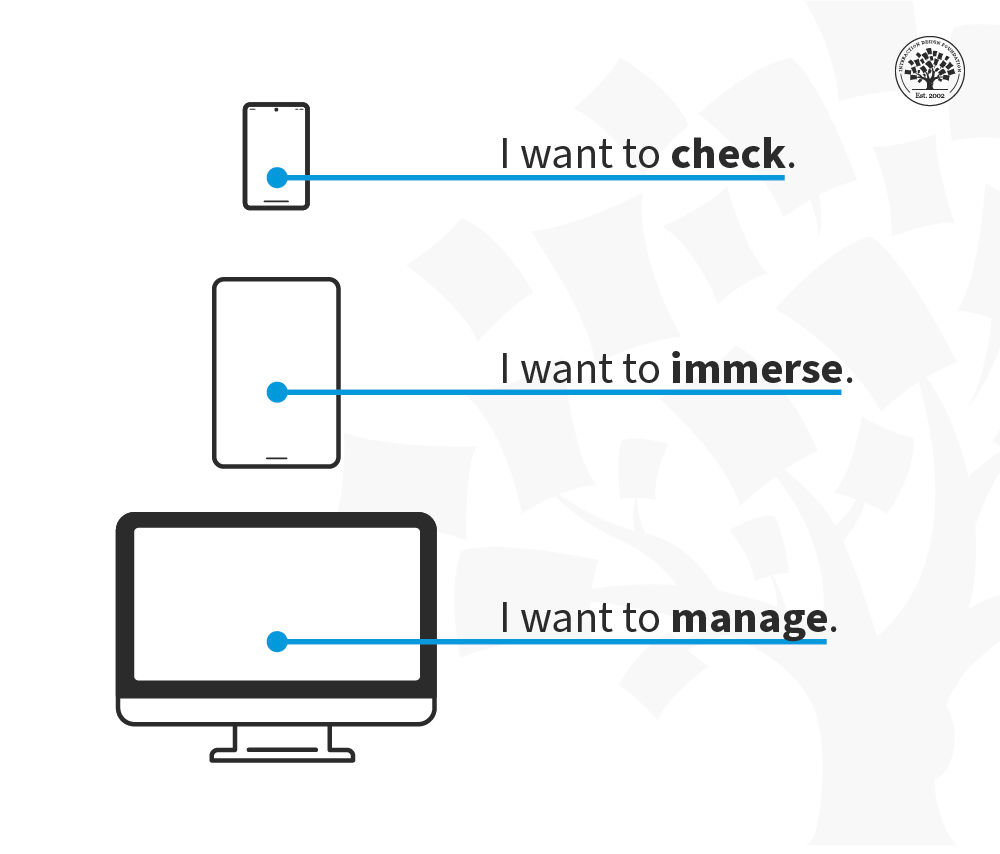

Whitney Hess, an HCI designer and UX consultant, proposes a broader model of context for mobile devices and a hierarchy that links mobile to other devices available to a user. Instead of looking at devices from a location perspective (mobile is on-the-go, a desktop is at the desk, and a tablet is on a flight), we look at devices from the perspective of what the user wants to achieve.

“CONTEXT IS KING…the physical context of use can no longer be assumed by the platform, only intentional context can… I have learned to see devices as location agnostic and instead associate them with purpose—I want to check (mobile), I want to manage (desktop), I want to immerse (tablet). This shift away from objective context toward subjective context will reshape the way we design experiences across and between devices, to better support user goals and ultimately mimic analog tools woven into our physical spaces.”

— Whitney Hess, in A List Apart

This model summarizes the difference between platforms. The mobile context is one of shorter interactions “checking” where you might dip in and out of a social network, seek an address or scan your email but don’t want to do anything particularly complex.

The tablet is mainly a leisure device (though it has its enterprise context, too) and provides a chance to immerse in an experience without becoming overly interactive.

Finally, the traditional desktop/laptop platform is where people manage their overall experiences on(and off)line.

This contextual model represents the user’s intentions rather than their physical location, and while there may be some shift between levels on each device, the main intent of each platform is clear.

The answer is research. Smartphone usage is incredibly diverse. Mobile users include a broad range of physical and cognitive abilities, language fluency, and cultural and geographical differences. Just as one size doesn’t fit all devices, one UX strategy doesn’t serve all communities.

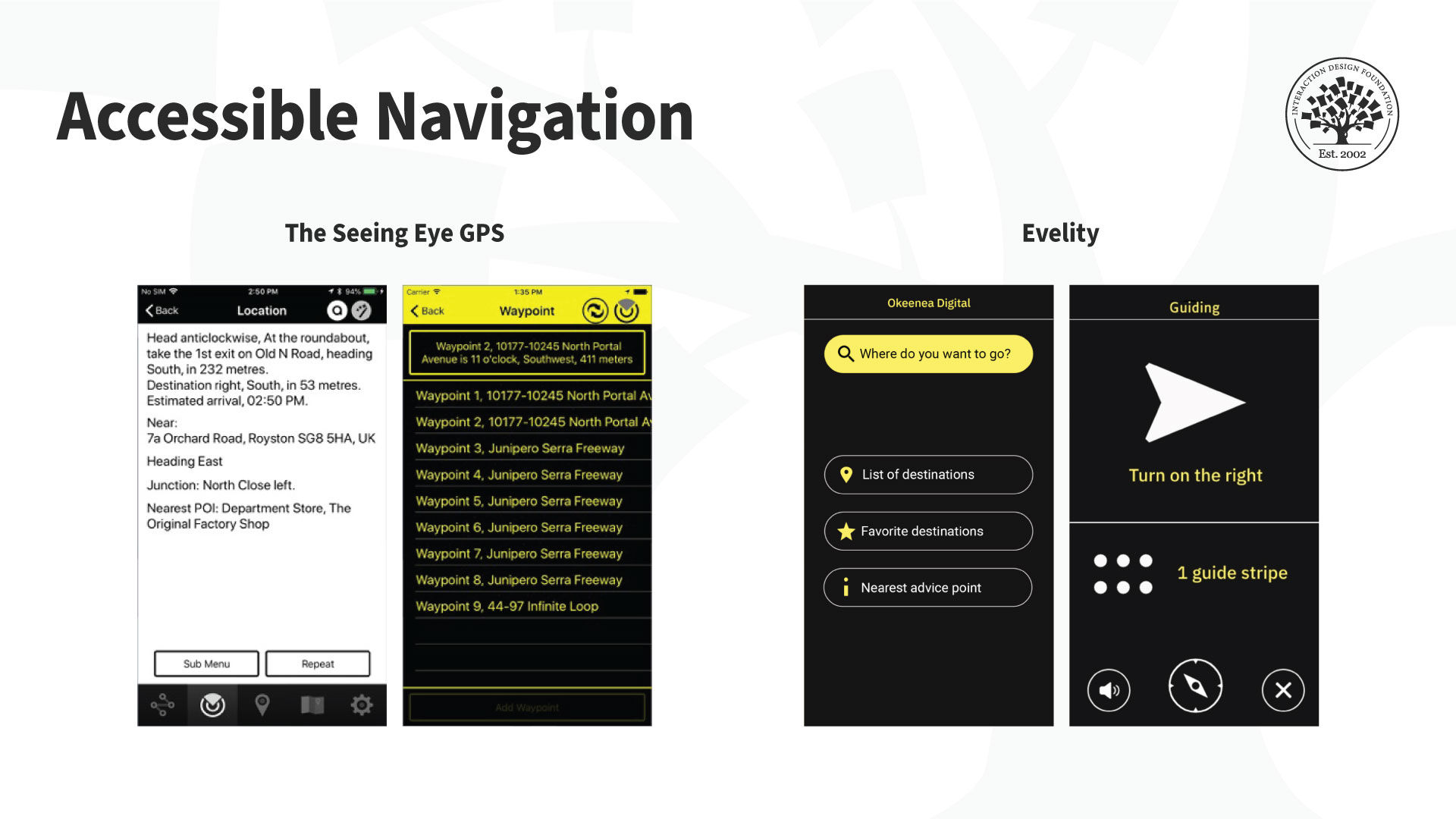

For instance, what do you need to know about an underrepresented community or users that are usually left out? For example: What do visually impaired users need to navigate your pages? IOS and Android devices have screen readers built-in, which helps them interact with smartphones. So, remember that you will have visually impaired users who rely on VoiceOver (on iOS) and TalkBack (on Android) to interact with your solutions.

Field studies will help you understand what else users do: their challenges and how they usually confront them.

The following video is a fantastic example of how well-designed, accessible experiences enrich people's lives. Notice how the video itself is extremely accessible; the voice-over helps a person with visual impairment experience the video.

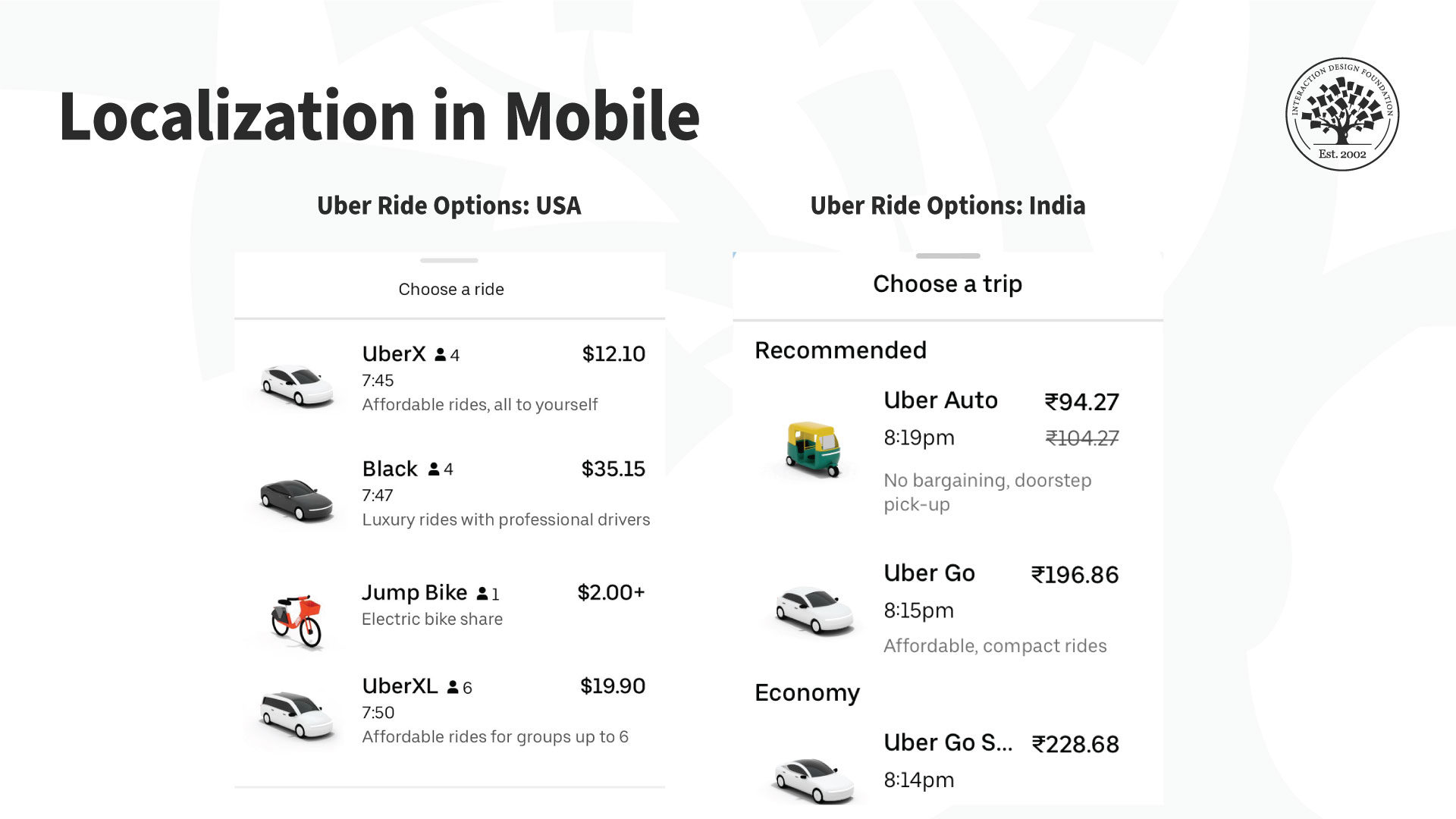

Another use case is if your app targets a non-local market. In that case, you will need to understand the cultural factors (national and regional nuances) and your audience’s cultural needs, constraints, and opportunities. You must localize your product. A simple translation is not enough for localization; in other words it’s not enough to adapt an application for local contexts. Some terms can get lost in translation—or they can sound illogical or offensive. So there’s more to local contexts than language. You might need to tweak some features or introduce new ones by region.

Context of use for mobile is essential to build a successful mobile UX. Mobile interactions change with physical, social, emotional, and cultural contexts. As a designer, you need to know where, when, why, and under what conditions and constraints users interact with your app, or mobile content. These insights will guide the design, layout, and overall UX strategy.

To learn more about the context of use for mobile, read Design Sketch: The Context of Mobile Interaction by Savio and Braiterman.

For a detailed look at accessibility, take the course Accessibility: How to Design for All.

Check out Frank’s short webinar on designing context-aware experiences (~40 minutes).

Hero image: © Interaction Design Foundation, CC BY-SA 4.0